Category: Uncategorised

Introduction to the Theme

The Walls Within

Working with Defenses against Otherness

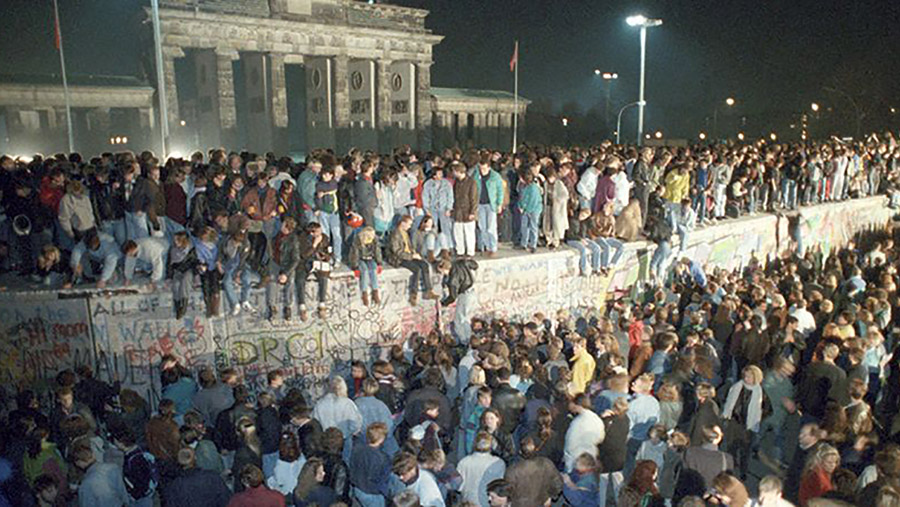

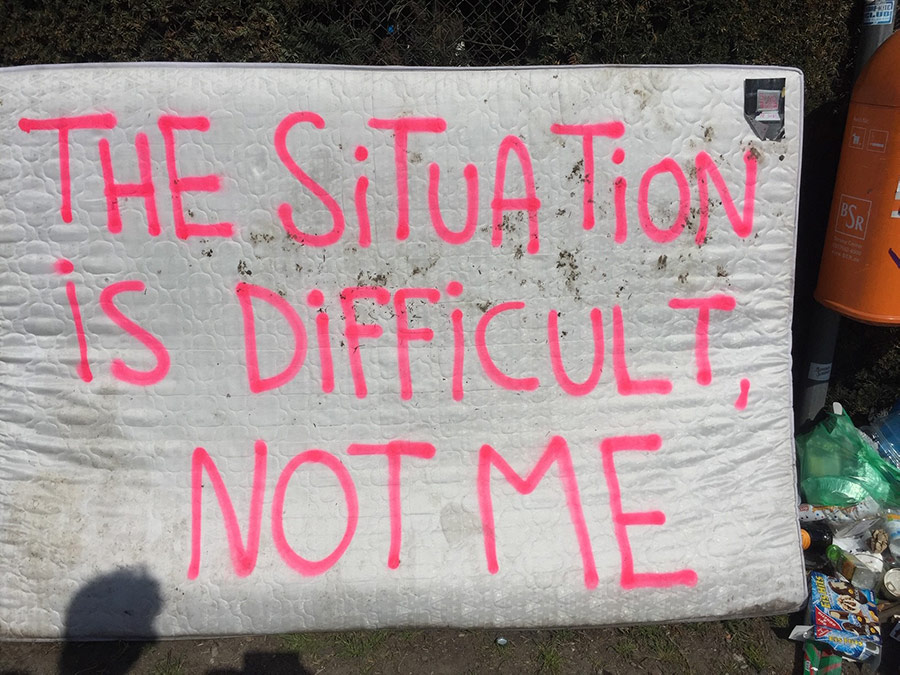

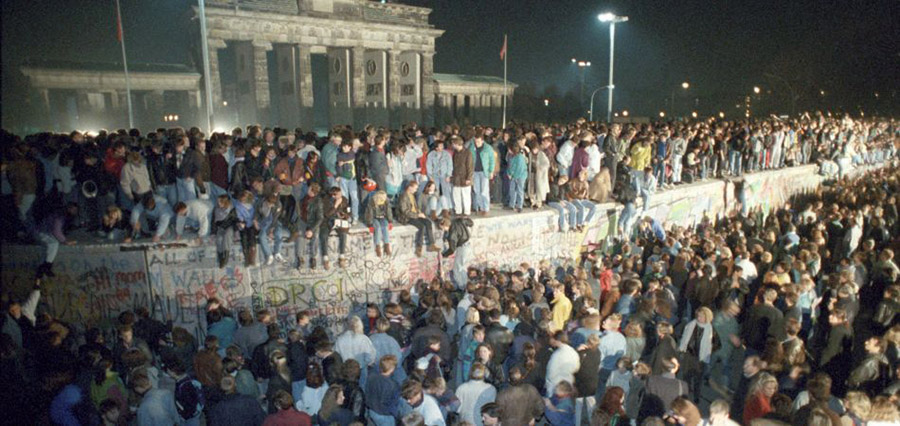

Walls – internal or external – are not clearly good or bad: The German Democratic Republic’s leaders declared the Berlin wall as a “peace border” and an “anti-fascist barrier” though in fact being a closed border for most of its citizens. In the original sense, a wall is an essential part of masonry, a structure of stones used for external security forming the foundations of homes and surrounding the places in which we build trust in each other. Interestingly, there are many different kinds of walls: For many Jews, the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem symbolizes the eternal, existing covenant of God with his people. The Chinese Wall is a symbol of the country’s innovative power, while the Berlin Wall has nowadays become a symbol of the peaceful overcoming of the German division. Yet, conspiratorial circles can form protective walls in free thinking remains possible like those against the Nazi dictatorship around the German army officer Stauffenberg or the White Rose Group around Sophie Scholl.

Whilst walls may provide protection, however, they can also function to keep the stranger at a distance, excluding ‘otherness’ in prisons, camps, or in the many subtle forms of everyday discrimination. How do the new walls drive thinking back to days long gone? Even when the ‘outer walls’ promoted by neo-authoritarian or populist leaders and their ideologies are not omnipresent, they contribute to ‘inner walls’ in the form of a sense of identity that suppresses and excludes critical disagreement in order to protect a pseudo oneness that extinguishes separation and difference within. When do walls support freedom – and when do they become an impediment to freedom?

Quite often walls are not made of bricks but of fantasies or signs and work as a projection screen. Freud’s clinical experience led him quite early to the insight that perceptions tend to cover other thoughts by projecting fantasies on top of each other. Still, unlike the projection of fantasies, Freud showed in The Interpretation of Dreams how speaking, that is, the transmission of desire, must prevail against an inner wall – he called it censorship instance. In the dream, this succeeds when the unconscious wish acquires recognition through something indifferent – the day’s remnants – under the condition that this indifferent is organized in a symbolic system. In Beyond the Pleasure Principle Freud came to think about a death drive which can be understood as a longing for pure immediacy. This striving, however, demands the annihilation of the symbolic and imaginary mediating processes by which people coordinate their dynamic and complex relations. We can see this in the shift away from a desire for what-is-yet-to-be-known towards an immediacy of affect which appears, f.ex., in digital aids that are based not on writing but on pictures, icons, sounds and voices and thus make reading skills more or more superfluous. As a result the complexities of politics, literacy, sexuality and ecosystems might soon become obsolete. Can this mean the end of psychoanalytic explorations, too?

Against the background of these social and technical changes associated with New Work, Industry 4.0 or digitization, there is a vivid discussion amongst ISPSO members about ‘contemporary’ psychoanalysis. This seems legitimate and may also lead to questions like these: What effect does it have on the boundaries between therapy and coaching when increasing numbers of clients are suffering from symptoms of strain due to the rising levels of stress and pressure at work? Or, in terms of organizations and their ecosystems: How can we as psychoanalytic consultants and coaches take up relations to the unconscious desire of the citizen-client that has become crucial for the development of digitised markets? In following their desires, not only do existing walls around markets and defenses against innovations fall, but further questions can emerge that challenge the one-sided assumptions engendering economic inequities, gender equity, or climate change.

We would like to invite you to contribute to an exciting program in which we can explore these and other issues, to get a broader understanding of the walls within as defenses against anxiety, innovation, and otherness. To explore together on our psychoanalytical contribution to working with defenses against the walls within inside of each one of us as well as in our communities, organizations, and in society.

Berlin Gallery

The Venue

Spreespeicher is an unique location with view onto the Oberbaumbrücke at Berlin’s Eastern Harbour. Located between Kreuzberg and the trendy media district Friedrichshain, not far from MTV, Universal Music, and the East Side Gallery – the longest remaining part of the Berlin Wall. The distinctive architecture of the landmarked warehouse looks back on a history of over 100 years and gives the building a unique appearance.

Spreespeicher

Stralauer Allee 2

10245 Berlin Germany

Venue Website